Welcome to our blog!

- By Glynn Borders

- •

- 04 Dec, 2017

- •

We intend to submit fun facts and information about Josephine Baker. We

will bring you, from time to time, anniversaries, quotes, tid-bits,

stories, photographs and the occasional update on the progress of our

production. THE DARK STAR FROM HARLEM opens at La Mama Experimental

Theater, New York, Fall, 2019.

Why Josephine Baker?

Here’s my long answer.

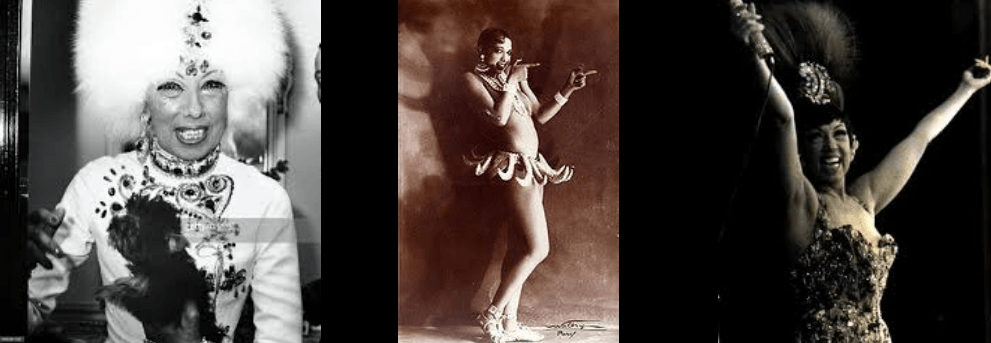

I grew up in Detroit, Michigan, right across the river from Windsor, Ontario, Canada. We got their TV channels and they got ours. I loved watching Canadian football and local shows like, “The Friendly Giant” and “Swingin’ Time” with Robin Seymour, our version of America Bandstand. The CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company) syndicated shows from the United Kingdom and we watched Monty Python a few years before it was an American thing. They also syndicated shows from France and they often broadcasted music hall performances of the amazing Josephine Baker. She was the first entertainer I ever watched in another language. It didn’t matter that I didn’t understand what she was saying or what she was singing about. But I got it. I was absolutely captivated by that strange old black lady with the long eye lashes and too much make up.

I began looking for her on Channel 9, always after midnight. Especially in the summer time. I couldn’t figure out why I liked her so much. Maybe it was the way she looked, so visually over the top. Maybe it was the way she sang, with such a uniquely sounding voice. Sometimes like a bird. Sometimes like a powerful force of nature. All the while, wearing a wide array of outrageous costumes. Long before Cher and many others. Every now and then she would blow my mind by singing in English. I was simply fascinated. Who was this old lady?

Unfortunately, there was on one in my family who shared my interest in this new discovery. They were not interested in late night television either. They preferred to asleep. We had a new color TV and an old black and white TV. I loved the old TV because there was no need to negotiate what to watch. My tastes were different anyway. I still love black and white. So, I watched everything alone. I watched science fiction movies, alone. I watched scary movies, alone, and I watched Josephine Baker, alone.

Why Josephine Baker?

Here’s my long answer.

I grew up in Detroit, Michigan, right across the river from Windsor, Ontario, Canada. We got their TV channels and they got ours. I loved watching Canadian football and local shows like, “The Friendly Giant” and “Swingin’ Time” with Robin Seymour, our version of America Bandstand. The CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company) syndicated shows from the United Kingdom and we watched Monty Python a few years before it was an American thing. They also syndicated shows from France and they often broadcasted music hall performances of the amazing Josephine Baker. She was the first entertainer I ever watched in another language. It didn’t matter that I didn’t understand what she was saying or what she was singing about. But I got it. I was absolutely captivated by that strange old black lady with the long eye lashes and too much make up.

I began looking for her on Channel 9, always after midnight. Especially in the summer time. I couldn’t figure out why I liked her so much. Maybe it was the way she looked, so visually over the top. Maybe it was the way she sang, with such a uniquely sounding voice. Sometimes like a bird. Sometimes like a powerful force of nature. All the while, wearing a wide array of outrageous costumes. Long before Cher and many others. Every now and then she would blow my mind by singing in English. I was simply fascinated. Who was this old lady?

Unfortunately, there was on one in my family who shared my interest in this new discovery. They were not interested in late night television either. They preferred to asleep. We had a new color TV and an old black and white TV. I loved the old TV because there was no need to negotiate what to watch. My tastes were different anyway. I still love black and white. So, I watched everything alone. I watched science fiction movies, alone. I watched scary movies, alone, and I watched Josephine Baker, alone.

Like most performers, Josephine Baker was influenced by her family, surroundings and social environment. Her childhood is well documented, but I was always curious about what music she listened to as a child. Born in 1906, she was immersed in ragtime, which was the one of the most popular musical forms of that time. Ragtime, made famous by Scott Joplin, came out of the military and marching bands that performed in parades – and there were always parades! We sometimes forget that war was a constant theme in the latter half of the 19th century into the 20th. Scott Joplin’s music combined the “four square” feel of patriotic marches with the sway and swagger of southern music out of Texas where he was born.

The two other music styles that were in vogue in the early 1900s were the tango and the waltz. Inspired by anything south of the border, Americans took to the tango with gusto. It allowed a type of sensual freedom not often seen outside of brothels. The waltz had been dominant for a hundred years and was firmly entrenched in American and European culture. Those who wanted to emulate the elites of society danced the waltz. Those who wanted to add more spice to their experience danced the tango. On top of all of this came the blues, popularized by W. C. Handy. He didn’t invent the blues, but gave it its current form which is still the norm today. The blues added deep low-down emotion to the mix that found favor with whites and blacks alike. Northern blacks found that the music reminded them of home in the rural south. Whites found the blues exotic because it employed notes and techniques not found in the typical music of the day.

By the time Josephine Baker was ten years old, the mixture of music from John Philip Souza (1854-1932), Scott Joplin (1868-1917) and W. C. Handy (1873-1958) as well as Latin music was in full swing. A list at the top 75 songs in America in 1916 reveals a variety of styles from classical to blues.

1

John McCormack

Somewhere a Voice is Calling

1916

US Billboard 1 - Jan 1916 (9 weeks), Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999 (1915), Brazil 27 of 1917

2

Billy Murray

Pretty Baby

1916

US Billboard 1 - Oct 1916 (6 weeks), ASCAP song of 1916, Brazil 29 of 1918

3

Al Jolson

I Sent My Wife to the Thousand Isles

1916

US Billboard 1 - Sep 1916 (7 weeks), Brazil 20 of 1918

4

Billy Murray

I Love a Piano

1916

US Billboard 1 - Apr 1916 (8 weeks), Brazil 23 of 1917

5

John McCormack

The Sunshine of Your Smile

1916

The two other music styles that were in vogue in the early 1900s were the tango and the waltz. Inspired by anything south of the border, Americans took to the tango with gusto. It allowed a type of sensual freedom not often seen outside of brothels. The waltz had been dominant for a hundred years and was firmly entrenched in American and European culture. Those who wanted to emulate the elites of society danced the waltz. Those who wanted to add more spice to their experience danced the tango. On top of all of this came the blues, popularized by W. C. Handy. He didn’t invent the blues, but gave it its current form which is still the norm today. The blues added deep low-down emotion to the mix that found favor with whites and blacks alike. Northern blacks found that the music reminded them of home in the rural south. Whites found the blues exotic because it employed notes and techniques not found in the typical music of the day.

By the time Josephine Baker was ten years old, the mixture of music from John Philip Souza (1854-1932), Scott Joplin (1868-1917) and W. C. Handy (1873-1958) as well as Latin music was in full swing. A list at the top 75 songs in America in 1916 reveals a variety of styles from classical to blues.

1

John McCormack

Somewhere a Voice is Calling

1916

US Billboard 1 - Jan 1916 (9 weeks), Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999 (1915), Brazil 27 of 1917

2

Billy Murray

Pretty Baby

1916

US Billboard 1 - Oct 1916 (6 weeks), ASCAP song of 1916, Brazil 29 of 1918

3

Al Jolson

I Sent My Wife to the Thousand Isles

1916

US Billboard 1 - Sep 1916 (7 weeks), Brazil 20 of 1918

4

Billy Murray

I Love a Piano

1916

US Billboard 1 - Apr 1916 (8 weeks), Brazil 23 of 1917

5

John McCormack

The Sunshine of Your Smile

1916

Josephine Baker arrived in Paris seven years after the first world war. She brought a new form and freedom and joy that Parisians could have never imagined.

During the invasion of the Nazis, in the second world war, Josephine remained in her beloved Paris. She did not flee to America, and instead, served with the French resistance. She was an intelligence liaison, basically, a courier-spy, carrying military coordinates across the country-side, with the new technology of the day. Invisible ink on her sheet music. After all, she was simply a musician. She was also an ambulance driver. After the war, General Charles de Gaulle awarded her with the Medal of the Resistance and the Legion of Honor, the two highest honors in France.

Josephine was also active in the civil rights movement in the United States. She wrote articles and gave lectures protesting segregation. When offered $10,000.00 to perform in Miami, she refused unless the audience was integrated. She succeeded. During that visit a man called her the “N” word at a hotel. Josephine Baker made a citizen’s arrest and the man was fined one hundred dollars. The National Association For The Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) awarded her with the Most Outstanding Woman of The year and declared May 20th, 1951, Josephine Baker day.

On August 28, 1963, Josephine was the only woman to speak at the famous, March on Washington, proudly wearing her Legionnaire’s uniform and her medals. That same day, the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. presented his legendary, “I Have A Dream” speech.

During the invasion of the Nazis, in the second world war, Josephine remained in her beloved Paris. She did not flee to America, and instead, served with the French resistance. She was an intelligence liaison, basically, a courier-spy, carrying military coordinates across the country-side, with the new technology of the day. Invisible ink on her sheet music. After all, she was simply a musician. She was also an ambulance driver. After the war, General Charles de Gaulle awarded her with the Medal of the Resistance and the Legion of Honor, the two highest honors in France.

Josephine was also active in the civil rights movement in the United States. She wrote articles and gave lectures protesting segregation. When offered $10,000.00 to perform in Miami, she refused unless the audience was integrated. She succeeded. During that visit a man called her the “N” word at a hotel. Josephine Baker made a citizen’s arrest and the man was fined one hundred dollars. The National Association For The Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) awarded her with the Most Outstanding Woman of The year and declared May 20th, 1951, Josephine Baker day.

On August 28, 1963, Josephine was the only woman to speak at the famous, March on Washington, proudly wearing her Legionnaire’s uniform and her medals. That same day, the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. presented his legendary, “I Have A Dream” speech.

The economy in Paris was booming. It was an amazing comeback after the first World War. Paris was a happy place. Parisians began to embrace anything that was new and depicted freedom. Maybe that’s why the avant-garde became so popular. Non-traditional art forms began to spring up. Dada, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Surrealism and eventually African.

AFRICA AND THE AVANT-GARDE

A popular vacation for wealthy Parisians, in the 1920’s, was the African safari. African masks and sculptures, as souvenirs and investments, were suddenly all over Paris. They were as popular as any painting by Pablo Picasso, who, became infatuated with Africa. The African obsession became widespread amongst avant-garde artists, including Paul Colin, Jean Cocteau, Michel Leiris and many others. Under this influence they created the word, Negrophilia. Which literally means, love of the negro. This period also lead to the influx of African immigrants.

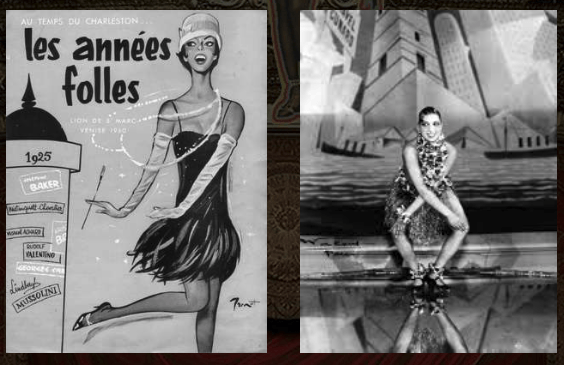

LA REVUE NEGRE, JAZZ AND THE CHARLESTON

A group of African-American musicians, singers and dancers were assembled to create, La Revue Negre. The Negro Review. With them, in 1925, was a nineteen-year-old chorus girl named, Josephine Baker. Their mission. Introduce Paris to a brand-new music called jazz and a hot new dance called, the Charleston. Jazz musicians were known as improvisational artists, so once, again, freedom was the name the of the game. To Parisians, nothing represented freedom more than dancing the Charleston, often in the streets and without music. They would simply say to one another, “hey-hey”, and everyone danced to the music in their hearts.

AFRICA AND THE AVANT-GARDE

A popular vacation for wealthy Parisians, in the 1920’s, was the African safari. African masks and sculptures, as souvenirs and investments, were suddenly all over Paris. They were as popular as any painting by Pablo Picasso, who, became infatuated with Africa. The African obsession became widespread amongst avant-garde artists, including Paul Colin, Jean Cocteau, Michel Leiris and many others. Under this influence they created the word, Negrophilia. Which literally means, love of the negro. This period also lead to the influx of African immigrants.

LA REVUE NEGRE, JAZZ AND THE CHARLESTON

A group of African-American musicians, singers and dancers were assembled to create, La Revue Negre. The Negro Review. With them, in 1925, was a nineteen-year-old chorus girl named, Josephine Baker. Their mission. Introduce Paris to a brand-new music called jazz and a hot new dance called, the Charleston. Jazz musicians were known as improvisational artists, so once, again, freedom was the name the of the game. To Parisians, nothing represented freedom more than dancing the Charleston, often in the streets and without music. They would simply say to one another, “hey-hey”, and everyone danced to the music in their hearts.